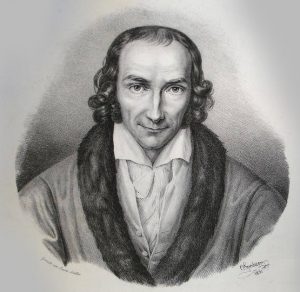

Johann Ernst Stapf (9 September 1788 – 10 July 1860) was a German orthodox physician who converted to homeopathy to become a pupil and colleague of Samuel Hahnemann, and a member of Hahnemann’s Provers’ Union.

Johann Ernst Stapf (9 September 1788 – 10 July 1860) was a German orthodox physician who converted to homeopathy to become a pupil and colleague of Samuel Hahnemann, and a member of Hahnemann’s Provers’ Union.

Stapf, together with Gustav Wilhelm Gross, was one of the first of Samuel Hahnemann’s pupils and throughout his career adhered to what he considered to be a pure, Hahnemannian form of homeopathy.

In 1822 Stapf was the co-founder, alongside Moritz Wilhelm Muller, of the first homeopathic journal, Archiv Für Die Homöopathische Heilkunst (Archive for the Homeopathic Healing Art).

Stapf taught William and Robert Wesselhoeft. He was also a colleague of Clemens Maria Franz Baron von Boenninghausen, Ernst von Brunnow, Harris F. Dunsford, Carl Franz, Philip Wilhelm Ludwig Greisselich, Gustav Wilhelm Gross, Carl Georg Christian Hartlaub, Frantz Hartmann, Christian Gottlob Hornburg, Christian Freidrich Langhammer, Georg August Heinrich Muhlenbein, Alphonse Noack, Karl Friedrich Gottfried Trinks and many others.

In 1806 Stapf entered Leipzig University, graduating in 1810 with a dissertation titled De Antagonismo Organico Meletemata. He moved to Naumburg in 1811 where he established himself in practice.

According to Pierre Augustus Rapou:

“Stapf is the most ancient disciple of Samuel Hahnemann and more celebrated than the others. He commenced to study Homeopathy in 1811, and in 1812 practiced only with the remedies mentioned in the first volume of the Materia Medica Pura. He was at the time the only partisan of our method, and he developed it well.”

Stapf was an early pioneer in homeopathic therapeutics. It was reported that he used olfaction of the higher potencies to administer the remedies. He commenced his studies of the high potencies in 1843 and published the results in June 1844.

Frantz Hartmann, in his account of the original Provers’ Union in 1814, wrote:

“Stapf was no longer living in Leipsic, but only came occasionally from Naumburg, where he was settled. The benevolence beaming from his eyes readily won for him the hearts of all.

“A more intimate acquaintance with him soon showed that in every respect he was far in advance of us in knowledge, although he had not long been honored with the title of doctor, and the regard was awarded to him unasked for, which was due to his extensive scientific achievements and his natural talents as a physician.

“His conversation was instructive in more respects than one, and he seemed hardly conscious of his superiority over others, while he was all the more esteemed on account of this very modesty.”

In 1822 Stapf started the first homeopathic journal, Archiv Für Die Homöopathische Heilkunst (Archive for the Homeopathic Healing Art). This was published in Leipzig three times a year and Stapf served as its editor until 1839.

He also published a number of pamphlets on the subject of Homeopathy. In 1829 he collected and edited the writings of Samuel Hahnemann, which he issued under the title Kleine Medicinische Schriften von Samuel Hahnemann. Stapf’s collection of Hahnemannian writings was translated and revised with additional texts and published in 1852 as The Lesser Writings of Samuel Hahnemann by English homeopathic physician Robert Ellis Dudgeon. This book was presented to Hahnemann on the occasion of his fiftieth Doctor Jubilee on August 10, 1829.

In 1830, Stapf was invited by another of Hahnemann‘s students, Harris Dunsford, to attend Queen Adelaide, and saved her life after her allopathic physicians had given up on her. As a result, this incredible cure “opened up the mansions of the aristocracy” across Europe to homeopathy.

According to Robert Ellis Dudgeon, two of Hahnemann‘s letters that had been in the possession of Dunsford at the time of his death in 1847, including one Hahnemann wrote to Johann Christoph Arnold, his publisher in Dresden, were likely given to him by Stapf. Dudgeon concluded from this that Stapf and Dunsford were friends.

In 1846 Stapf published Additions to the Materia Medica Pura. This was a collection of the provings originally published in the first fifteen volumes of the Archiv Für die Homöopathische Heilkunst .

Stapf wrote for the Archiv Für die Homöopathische Heilkunst under the nom de plume of ‘Philalethes.’ In the sixth volume of the Archiv there are several essays by Philalethes, and in one of them he describes how his conversion to Homeopathy occurred after reading The Organon shortly after its first publication in 1810.

Hahnemann frequently corresponded with Stapf about the articles in the Archiv. In a letter to Stapf, written in 1826, he wrote:

“I still continue to read works on other scientific subjects, but nothing medical except your Archiv Für die Homöopathische Heilkunst . I have not read even Christoph Wilhelm von Hufeland‘s Journal for years, and, in my present isolation and severance from well informed physicians, I do not know where to get the loan of the number of Christoph Wilhelm von Hufeland‘s Journal you refer me to.

Hahnemann recognized the value of Stapf’s publication in promoting the unadulterated homeopathy that they both adhered to, especially as newer homeopaths began experimenting with hybrid forms of medicine that deviated from Hahnemann’s purist medical doctrine:

“I fear more the empirical contaminations of that society of half Homoeopaths about which you write, which they had sufficient prudence not to invite me to join, but of whose doings I have been pretty correctly informed by oral communications. I fear that inaccuracy and rashness will preside over their deliberations, and I would earnestly beg of you to do what you can to check and restrain them.

“For should our art once lose its attribute of the most conscientious exactness, which must happen if the dii minorurn gentium seek to push themselves into notoriety by their so called observations, then I tremble for the raising of our art out of the dust; then we shall lose all certainty, which is of great importance to us.

“Therefore, I beg you will keep out of your Archiv Für die Homöopathische Heilkunst all superficial observations of pretended successful treatment. Admit only truthful, accurate, careful records of cases from the practice of accredited Homeopaths; these must be models of good Homeopathic art.

Johann Ernst Stapf died at Kösen, on July 11, 1860, in his seventy-first year. Lutze chronicled his passing:

“On the 11th of July, 1860, there died at Kosen the first and greatest scholar of Samuel Hahnemann, the Sachsisch Meining’sche Medizinalrath Johann Ernst Stapf, in his seventy first year. Peace to his ashes, and rest, now his long pilgrimage is over.”

Select Publications:

- Archiv Für die Homöopathische Heilkunst (Archive For the Homeopathic Healing Art) (1822-1843)

- Neues Archiv Für die Homöopathische Heilkunst (1843-1848)

- Additions to the Materia Medica Pura (1846)

Leave A Comment