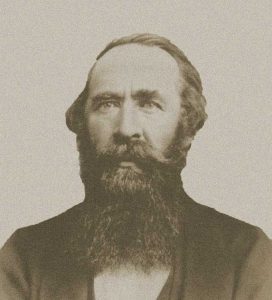

Ralph Barnes Grindrod LSA MD 1831 (19 May 1811 – 18 November 1883), was a British orthodox physician who, though proclaiming his absolute antagonism towards homeopathy, nevertheless worked alongside the homeopaths in the Malvern Hydrotherapy Establishment, where he closely observed the work of James Manby Gully and set out to expose the many allopathic practitioners who “secretly” came to the spa for homeopathic treatment.

Ralph Barnes Grindrod LSA MD 1831 (19 May 1811 – 18 November 1883), was a British orthodox physician who, though proclaiming his absolute antagonism towards homeopathy, nevertheless worked alongside the homeopaths in the Malvern Hydrotherapy Establishment, where he closely observed the work of James Manby Gully and set out to expose the many allopathic practitioners who “secretly” came to the spa for homeopathic treatment.

Grindrod was born in Cheshire in May 1911. He received his Licentiate from the Society of Apothecaries in 1830, and later studied at Cambridge (1844) and Erlangen (1851). In 1855 he was awarded an honorary M.D. (Lambeth) from the Archbishop of Canterbury.

In 1830 Grindrod was working as medical officer for working men’s clubs near Runcorn in Cheshire where he became increasingly concerned at the alcohol-fueled, disorderly conduct of the men at their monthly meetings. Grindrod became an activist in the Temperance Movement.

He relocated to Manchester and served as a committee member of the Manchester Temperance Society. However, he thought moderation was insufficient and in 1834 became the first medical man in Britain to sign the pledge of abstinence.

Grindrod became a leading figure in the total abstinence movement and in 1836 was elected President of possibly the first provincial abstinence organization, The Manchester and Salford Temperance Society.

In addition to his commitment to eradicating drunkeness, Grindrod was also concerned with the plight of seamstresses. He was also a colleague of philanthropic factory owner and social reformer Robert Owen.

Grindrod practiced water therapy at Townshend House, Malvern, which he combined with orthodox medicine. He was also a member of the Geological Society, and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society,

Although not a Freemason himself, Grindrod opened his house to the Provincial Grand Lodge of Worcestershire in December 1867 where they consecrated the new Malvern Royds Lodge.

Grindrod and his wife Mary had one son, the surgeon Charles Frederick Grindrod (1847 – 1910) who was born on the Isle of Wight. Charles, who lived in Malvern Wells, was a friend of Elgar and the author of Malvern What to See and Where to Go (1894).

Grindrod retired in the early 1880s and lived with his son in Malvern Wells, where he died aged 72 in 1883.

Select Publications:

- Bacchus. An Essay on the Nature, Causes, Effects, and Cure of Intemperance (1839)

- Course of three lectures on the physiological effects of alcohol on the human system, delivered … in the Theatre Royal, Whitehaven, on … 1st, 2nd and 3rd Sept., 1845 (1845)

- The Slaves of the Needle: An Exposure of the Distressed Condition, Moral and Physical, of Dress-makers, Milliners, Embroiderers, Slop-workers, &c (1845)

- Medical Discussion on Teetotalism (1847)

- Malvern: Past and Present; Its History, Legends, Topography, Climate, etc (1865)

- Malvern: Its Claims as a Health Resort (1871)

- A Physician’s Thoughts on Scriptural Temperance (posthumous, 1884)

- The Nation’s Vice: The Claims of Temperance on the Christian Church (posthumous, 1884)

Of Interest:

Beginning in October 1861, Grindrod was involved in a series of letters in the British Medical Journal in which he sought to distance himself and his practice from charges that the Malvern hydropathic community was awash with homeopaths.

On 12 October he wrote to the British Medical Journal to defend himself following an anti-homeopathic article the previous month. He explained that due to his hard work and expertise combining water therapy and orthodox medicine he had managed to build a large and successful practice during more than 12 years at Malvern. However, he explained that he did not owe:

On the contrary, Grindrod continued:

Curiously, he pointed out, his allopathic colleagues sent all their patients requiring hydrotherapy not to him but to his Malvern homeopathic-hydropathic competitors. He added:

Even more astonishingly, Grindrod expressed his surprise at seeing allopathic physicians turn up for treatment at homeopath James Manby Gully’s establishment, and to consult with Gully over “difficult cases,” even to bring and send their own patients to see Gully, all the while protesting against homeopathy!

In his letter Grindrod mentioned the following colluding allopaths by name: Booth Eddison, the President of the British Medical Association (a patient of James Manby Gully’s), Benjamin Vallance of Brighton (President of the Medico Chirurgical Society, Surgeon at the Sussex County Hospital), Thomas Spencer Wells, John Addington Symonds of Bristol (Vice President and President of the British Medical Association), Robert Lee and Sutherland (possibly sanitary reformer Dr. John Sutherland), and a distinguished physician from the Consumption Hospital. As a result, Grindrod observed, this:

Clearly Grindrod had struck a nerve. In a subsequent letter to The British Medical Journal on 26 October 1861, he complained bitterly about the way Thomas Spencer Wells denounced homeopathy from his position as Editor of the Medical Times and Gazette, and then turned up in secret to place himself under the care of a homeopath – James Manby Gully.

‘Now sir, I, a resident practitioner in Malvern, year by year and month by month witness practitioners of the legitimate school of medicine coming down to this place, denouncing in public the homeopathic system as one of unmitigated humbug, and placing themselves under the care of professed homeopathic practitioners…’

Grindrod continued that Thomas Spencer Wells‘ claim that James Manby Gully “is not a homeopath” was totally untrue. He noted that Gully was listed in the Homeopathic Medical Directory for 1855 and 1861, and Gully’s two assistants and his other partners at Malvern were also homeopaths, James Smith Ayerst, John Chapman, Walter R Johnson (who replaced Grindrod as Editor of the Journal of Health), and James Wilson). Another homeopath, James Loftus Marsden, in partnership with Gully at Malvern had, according to Grindrod, prescribed homeopathically for Gully and his family.

Grindrod then addressed Wells’ accusation that he was himself a homeopath, something Grindrod denied emphatically. However, he acknowledged that:

“Some ten years ago, numbers of my patients and friends urged upon me a study of homeopathic principles, and a trial of homeopathic medicines. At last I consented to read and experimentalise; and after a few weeks, or at most months, of quiet and unostentatious trial of homeopathic remedies (possibly, as some of my homeopathic friends tell me, inefficiently carried out), I arrived at a practical result, that I could not conscientiously become a disciple of Hahnemann.

I can therefore, boldly and unequivocally assert that I have never either been a believer or a practitioner in homeopathy. I have full reason to believe that my non adoption of homeopathic views has been a loss to me of at least a thousand pounds a year.”

Grindrod continues

“… dealings with homeopaths as water patients I have every hour of the day. Often ten out of twelve of the patients at my table are strenouous believers in homeopathy; not unfrequently homeopathic physicians place themselves under my care – but simply for the water treatment.

You cannot walk through the streets of Malvern, you cannot enter a house, nor visit a social party, in this famous watering place, without meeting a host of believers in homeopathy.

You can have but a limited idea of the extended influence of homeopathic belief in this place, and of the almost controlling power it exercises on professional advancement and medical success. He must indeed fight, as I have done, a hard battle, who would attain a successful position, and yet not be a homeopathist.

Now, sir, once and for all, I assert from personal knowledge, that the almost pervading influence of homeopathy in this place is mainly attributable to such individuals as Thomas Spencer Wells and others whom I have mentioned in my previous communication, and also to those ’eminent metropolitan physicians still alive’ who advised Thomas Spencer Wells and others to place themselves under the care of a homeopathic physician.”

On 30 November, Grindrod wrote once again to the British Medical Journal to “expose” James Manby Gully as a homeopath, a spiritualist, a mesmerist and a ‘charlatan’,

Evidently Grindrod was unable to let the matter rest. Over five years later, on 9 February 1867, Grindrod wrote again to the British Medical Journal. An article had appeared in the Malvern News entitled A Biographical Sketch of Dr. Wilson by James Manby Gully (James Wilson had recently died). In the article, Gully claimed that James Wilson had been vilified in the allopathic press, but Grindrod contested this vociferously.

Instead, Grindrod repeated his earlier assertions that Gully was a homeopath, a spiritualist, a mesmerist and all round clairvoyant, and he referenced his earlier letter to the British Medical Journal, adding to this the accusation that a Professor of University College, and an eminent London Surgeon and author were also under James Manby Gully‘s care at that time as well.

Leave A Comment