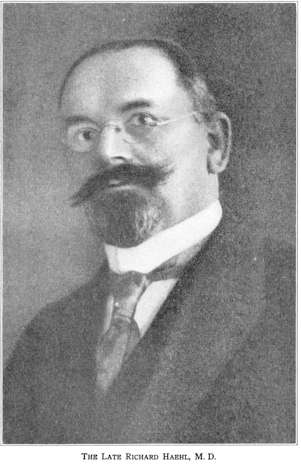

Richard Haehl M.D. (15 December 1873 – 7 February 1932), a German orthodox physician from Stuttgart and Kirchheim who converted to homeopathy, traveled to America to study homeopathy at the Hahnemann College of Philadelphia.

Richard Haehl M.D. (15 December 1873 – 7 February 1932), a German orthodox physician from Stuttgart and Kirchheim who converted to homeopathy, traveled to America to study homeopathy at the Hahnemann College of Philadelphia.

He become the biographer of Samuel Hahnemann, and the Secretary of the German Homeopathic Society, the Hahnemannia.

Haehl was responsible for saving many of the valuable artifacts belonging to Samuel Hahnemann and retrieved the 6th edition manuscript of the Organon, translating it and helping ensure it was finally published in 1921.

Haehl was the founder of the Hahnemann Museum, in Stuttgart, based at his home.

Richard Haehl was a student of Thomas Lindsley Bradford, and he was a colleague of William Boericke, John Henry Clarke, Paul Dahlke, Robert Ellis Dudgeon, Eberhard, Walter Hering, Alexander B Griffiths, Friedrich August Gunther, Leopold Suss Hahnemann, Stephen and Rosa Hobhouse, John Moorhead Byres Moir, Antoine Nebel, George B Peck, Pierre Schmidt, James Searson, Alfons Stiegele, Jarvis L Thorpe, Leon Vannier, James William Ward, William Wallace Winans, Hans Wapler, and Immanuel Wolf.

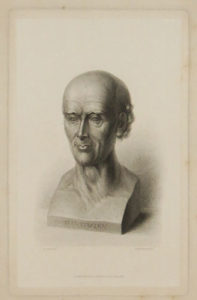

Bust of Samuel Hahnemann, created by David von Angers, 1837

German homeopath Dr Richard Haehl spent many years collecting anything of Samuel Hahnemann’s he could find. From 1921 to 1931 he exhibited the items he had accumulated in his house.

Judging by Haehl’s Visitors’ Book from the time, this seems to have become something of a place of pilgrimage for homeopaths from around the world. After Haehl’s death the collection, now owned by the industrialist and philanthropist Robert Bosch, was housed in the homeopathic hospital in Stuttgart.

Tragically, despite being moved for safe keeping during the Second World War, some of the larger objects were destroyed in a bombing raid in 1942. Thankfully the written material was being stored elsewhere – in a salt mine – and so was saved from bomb damage.

Among the collection was Hahnemann’s long-awaited sixth edition of the Organon, written in 1842. Twice the manuscript was in danger of being lost, once during the siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and once during the military over-running of Westphalia during World War I of 1914-18.

The sixth edition finally saw daylight in 1921 when Haehl, “translated” it into English and Boericke and Tafel published an English version. This resolved decades of dispute within the international homeopathic community over Hahnemann’s later theories and experimentation:

A year previously he had managed, with the financial support of the American homoeopaths William Boericke and James William Ward, to buy Samuel Hahnemann’s bequest (including the Organon manuscript) from the Boenninghausen family who had been owners of this “treasure” since Mélanie Hahnemann’s death in 1878.

In return for their generous financial help Haehl gave his American benefactors the original manuscript of the 6th edition of the Organon while he held on to a copy which Mélanie Hahnemann had had drawn up already in 1865. The copy might also be one which Mélanie Hahnemann’s adopted daughter Sophie, the wife of one of Boenninghausen’s sons, had commissioned in 1879.

Haehl used one of the two copies for his edition of the 6th edition published by Willmar Schwabe in 1921. Both copies have been considered lost ever since. They are not with Haehl’s collection which the German industrialist Robert Bosch had bought off him still during his lifetime.

The original which William Boericke used as the basis for his American translation of the Organon eventually found its way into the library of the University of California in 1971 and is still there today.

Josef M Schmidt’s 1992 publication of the Organon’s 6th edition is based on this still existent original manuscript which shows only few gaps in comparison to one of the copies that were available to Haehl for his edition.

Neither William Boericke in the preface to his translation, nor Haehl in the introduction to his edition refer to the significance of the new potentisation method described in § 270 of the 6th edition for Samuel Hahnemann’s therapeutic practice in the last years of his life and for homoeopathic pharmacotherapy in general.

Only in his very comprehensive Samuel Hahnemann biography Haehl remarks: “Samuel Hahnemann called remedy potencies that were produced in this new way Médicaments au globule as opposed to the Médicaments à la goutte which were produced using an earlier system and whose potency grades he used to express in Roman numerals. For the new remedy preparations on globules he used Arabic numerals with a little ring above (1,2,3,5 etc.)”

Haehl also mentions that according to Samuel Hahnemann’s then still existing medicine chest, these remedies were produced in ten different potencies. Which potentisation Samuel Hahnemann preferred, when and in which cases he resorted to the controversial Q-potencies and how often he actually used them Haehl was unable to disclose.

Haehl’s premature death prevented him from publishing Samuel Hahnemann’s case journals, which had not been published before and had originally not been intended for publication at all.

Richard Haehl thanked the following for assistance in writing Biography of Samuel Hahnemann in two Volumes: the daughter in law of Carl Julius Aegidi, the Prince of Anhalt Kothen, Lily Braun, Karl Schmidt Buhl, G A Schuler, Waschke, Privy Counsellor Wittig, and of course, his homeopathic colleagues.

Select Publications:

- Massage: Its History, Technique and Therapeutic Uses (1898)

- Samuel Hahnemann, Sein Leben und Schaffen (Samuel Hahnemann, His Life and Work) (1922)

- Gynäkologie und Homöopathie (Gynecology and Homeopathy) (1935)

Leave A Comment