Thomas Skinner L.R.C.S.E. M.D. [St. Andrews 1857] (11 August 1825 – 11 September 1906) was an allopathic physician and a strident opponent of homeopathy, who had worked very closely with Sir James Young Simpson as his private assistant in Edinburgh. Simpson regarded Thomas Skinner as his star pupil.

Thomas Skinner L.R.C.S.E. M.D. [St. Andrews 1857] (11 August 1825 – 11 September 1906) was an allopathic physician and a strident opponent of homeopathy, who had worked very closely with Sir James Young Simpson as his private assistant in Edinburgh. Simpson regarded Thomas Skinner as his star pupil.

Skinner subsequently became so ill he had to give up his medical practice, and he travelled to America, and worked on transatlantic liners as a medical officer, until he was finally completely cured of his ailments by homeopath Edward William Berridge. Skinner stayed with Berridge at Thomas Lake Harris‘s Fountain Grove commune.

After his conversion to homeopathy Thomas Skinner became one of the greatest homeopaths of his time. Skinner was a high potency prescriber, and he invented the Skinner Centesimal Fluxion Potentiser to make these remedies. In 1877 Skinner was awarded an Honorary Degree from the New York Homeopathic Medical College.

Skinner was the maternal grandfather of author, broadcaster and horologist, Lt. Cmdr Rupert Thomas Gould.

Thomas Skinner was born in August 1825, the second son of Edinburgh solicitor John Robert Skinner W.S. and his wife, Ann Black.

Skinner was educated in Edinburgh, obtaining his License from the Royal College of Surgeons (Edinburgh) in 1853 and his M.D. at St. Andrews in 1857. As a student Skinner excelled, particularly in the area of women’s diseases and obstetrics, for which he came to the attention of Sir James Young Simpson, Professor of Midwifery at Edinburgh and pioneer of the use of Chloroform anesthesia. For the rest of his career Skinner maintained that chloroform was “as safe as milk,” and in 1862 developed “Skinner’s Mask” for the administration of chloroform during anaesthesia.

During the 1851-2 session Skinner won Simpson’s Gold Medal. After qualifying, he spent three years in practice in Dumfriesshire, before becoming Simpson’s private assistant at 52 Queen Street, Edinburgh, in 1855-1856.

It was during this period that Skinner was front and centre for the “Simpson-Henderson controversy” when his mentor issued a very public refutation of his Edinburgh University colleague, William Henderson M.D. (1872), professor of general pathology, who had published favourable findings on homeopathy.

In the preface to Skinner’s 1876 book on Homeopathy and Gynecology, he acknowledged that he had been influenced by Simpson’s unscientific bias against homeopathy. However, Skinner also persisted with Simpson’s single remedy treatment for the rest of his medical career.

In 1859 Skinner relocated to Liverpool where he set up in private practice and served as Obstetric Physician at the Liverpool Lying-in Hospital. That year he married Hannah Hilton (1826 – 1897), daughter of a wealthy Lancashire manufacturer. They had two children, Hilton Skinner and Agnes Hilton Skinner (born using chloroform as an anaesthetic). Agnes would become the wife of composer William Monk Gould and mother of horologist, author and naval officer Rupert Thomas Gould.

While in Liverpool Skinner was an outspoken critic of homeopathy and was instrumental in the passing of what he later described as “the most illiberal law that ever was made by a profession styling itself as ‘liberal'” that prohibited homeopaths from membership of the Liverpool Medical Institution.

Due to overwork Skinner became seriously ill with influenza, leading to insomnia, gout, and constipation. He was forced to cease practice and eventually took up a position as medical officer on a transatlantic liner. Although he slowly recovered he was not cured and continued to suffer. It was at this point that Skinner was first properly introduced to homeopathy.

‘It was through correspondence about some matter apart from medicine that Dr. Skinner in 1873 became acquainted with Edward William Berridge; but the acquaintance led to a desire on Skinner’s part to know something about homeopathy, as he had heard of some good cures when over in America.

The upshot of it all was that Edward William Berridge prescribed Sulphur for our patient in the MM potency, prepared by William Boericke of Philadelphia. When Skinner felt the homeopathic remedy at work inside him it was a revelation indeed.

“I shall never forget the marvellous change which the first dose effected in a few weeks, especially the rolling away, as it were, of a dense and heavy cloud from my mind.”

He was cured of the constipation, the acid dyspepsia (which he had had all his life), sleeplessness, deficient assimilation and general debility, and restored to a life of usefulness and vigour.

Under Berridge’s tutelage, Skinner threw himself into the study of homeopathy, reading voraciously and studying Hahnemann’s three major works, The Organon, Materia Medica Pura, and Chronic Diseases. As a gynecological specialist Skinner also recognized the benefits of homeopathy for women, in contrast to the surgical interventions that then predominated:

“I at once hailed homeopathy, as every modest woman must, and as every right-minded physician ought, as that which wanted in order to roll back the fearful tide of mechanical interference in the treatment of the diseases of women, which is the greatest medical scandal of the age.”

In 1876 Skinner attended the International Homoeopathic Congress in Philadelphia. Upon his return to England he founded The Organon: A Quarterly Anglo-American Journal of Homeopathic Medicine and Progressive Collateral Science, with Berridge in the UK and Adolph Lippe and Samuel Swan in the USA.

Although it ceased publication after the first issue of Volume 4 in 1881, it became the pace setter for journals devoted to pure Hahnemannian homeopathy that followed — The Homeopathic Physician and The Medical Advance.

Inspired by Hahnemann and high potency American homeopaths, once back in Liverpool Skinner developed a centesimal fluxion machine for making high potency remedies. Skinner thus became an influential figure, connecting US and British homeopathy, and was often associated with other high-potency prescribers of that period, including Bernhardt Fincke, Samuel Swan, Adolph Lippe, Henry Newell Guernsey, William Boericke et al. These were homeopaths who were at the forefront of the development of the higher centesimal potencies and of investigating their clinical use in the period 1860-80 .

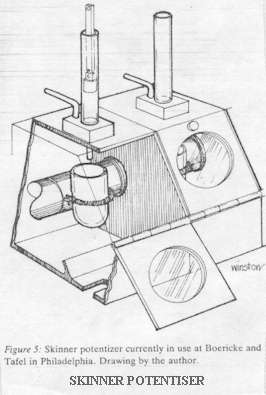

The “Skinner Centesimal Fluxion Potentiser” was first described in an article by Thomas Skinner, MD in The Organon (Vol. I, p. 45).

Very early on, Skinner was unsure if it was the dilution or the succussion which was the deciding factor in preparing remedies.

He conducted an experiment in which he took a two dram vial, and placed in it one drop of Sulphur tincture. He then filled the vial slowly. He then emptied it and repeated the process a thousand times.

When the next patient arrived that needed Sulphur, he gave a dose of the potency he had prepared. The patient had such a strong reaction that it had to be antidoted.

This was the starting point of developing a machine that would prepare remedies by a similar process.

The machine was designed to be used over a wash-basin in a doctor’s office. The water supply from the faucet was attached to the machine and provided the motive power through the “water wheel.”

The machine held two potentizing vials. The vials had a spherical bottom and each held just 100 minims of liquid.

The water supply was adjusted (with the stop-cocks) so that the vial was filled with 100 minims of water before overturning quickly and forcibly ejecting the contents into the sink and down the drain.

In theory, one drop was left adhering to the wall of the vial.

The vial what then returned to the upright position, and the process repeated.

Dr. Skinner wrote that because of all the ways of adjusting the water flow of the machine, that there was “no difficulty obtaining mathematical certainty” in the potencies. The machine could make 50 potencies a minute, 8,000 an hour, 72,000 per day, and a 100,000 (CM) in about 33 hours. An MM (a 1,000,000) could be made in 330 hours or 14 days.

He said that his “fluxion centesimal” (F.C.) potencies are made “by a process such as Hahnemann himself, if he could witness them, would highly approve, because all the essential points are most scrupulously observed and greatly improved upon, whilst time is enormously economized, and error is next to an impossibility, so perfect are the methods used.”

Skinner’s original machine was on display at the Faculty of Homeopathy Library in London. In about 1900, Boericke & Tafel installed a Skinner Machine in their New York City pharmacy.

Skinner continued to practice in Liverpool where he was, in the words of Henry C. Allen, “probably the best prescriber in Britain.” As an homeopath he continued to advocate for single remedies in prescribing. For his dedication to this pure Hahnemannian homeopathy Skinner was also very influential in India.

In 1881 the final volume of The Organon was published. That year Skinner relocated to London. He established residence at Waylands, Kent, in a large house called The Knoll. Skinner had a large, private homeopathic practice in the West End of London, at various addresses, for more than twenty five years, including 25 Somerset Street, Portman Square, and 6 York Place, Baker Street, before briefly at 115 Inverness Terrace, Bayswater.

For a short time Skinner became an assistant physician at the London Homeopathic Hospital, and in 1889 he became a member of The British Homeopathic Society.

From 1893 – 1895 he was also a member of the influential “Cooper Club,” the weekly dining group of leading “Hahnemannian” homeopaths, centred on Robert Thomas Cooper, James Compton-Burnett, and John Henry Clarke, who had introduced Skinner to the group. Skinner remained an occasional member of the club thereafter. For Clarke, Skinner was one of the three great living Hahnemannian homeopaths, alongside Cooper and Compton-Burnett.

Hannah died at Folkestone in July 1897, possibly while recuperating from illness. Skinner moved to central London where soon after he married Lilian, forty-three years his junior. Skinner died at their Inverness Terrace home following a fall, leaving Lilian as the sole beneficiary of his will.

Shortly after Skinner’s death John Henry Clarke wrote A Biographical Sketch of Dr. Skinner, noting Skinner’s role in introducing him to the world of higher potency prescribing. In the preface to his own Dictionary of Materia Medica Clarke also acknowledged his debt to Skinner, recounting how:

“One of the most precious words of congratulation on its completion came to me from himself. That I had succeeded in satisfying Dr. Skinner was to me praise indeed.”

Thomas Skinner’s Obituary was in The Indian Homeopathic Review and The Monthly Homoeopathic Review in 1906.

Select Publications:

- Fistula: Its Iodo-therapeutic Treatment (1859)

- The Granulation of Medicines (1862)

- Homoeopathy in its Relation to the Diseases of Women (1876)

- The Ethics of Mongrelism (1881)

- Dr. Skinner’s Grand Characteristics of the Materia Medica with John Henry Clarke (posthumous, 1931)

Of interest:

Richard Skinner Homeopathic Chemist at 138 High Street, Bromley, Kent is listed in The British, Colonial, and Continental Homeopathic Medical Directory in 1899, Chemist to the Bromley Homeopathic Dispensary,

Thomas Skinner’s older brother was Edinburgh lawyer, author and Town Clerk, William Skinner (1823 – 1901).

Dr Skinner gained a Licence to practice medicine from the RCSEd in 1853 then his MD from St Andrews in 1857, not 1853

What is the full form of L. R. C. S. Edinburgh?

Thank you for your question. The qualification awarded to Skinner was: Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons (Edinburgh).