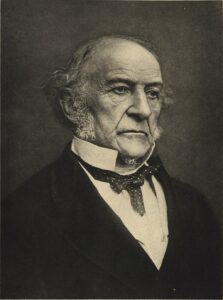

William Ewart Gladstone

Image Source: wikimedia.org

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS (29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British Liberal Politician, statesman and Prime Minister.

Gladstone was a patient of homeopaths James Manby Gully and Joseph Kidd. Gladstone’s Parliamentary adversary, the Conservative Party politician and Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, also became a patient of Kidd’s. On the day of Disraeli’s first visit to see Joseph Kidd, 7 November, 1877, he wrote in his journal, “Today I saw Dr Kidd who cured the Chancellor.”

Gladstone was a friend of John Stuart Blackie, whose father in law, James Wyld (father of another homeopath, George Wyld), was a close neighbour of Gladstone’s uncle Thomas. The Wylds and the Gladstones were intermarried.

In Antwerp, in February 1832, Gladstone and his brother John, who were undertaking a tour of the continent, became acquainted with the then Reverend and future homeopathic physician Charles Joseph Berry King. Gladstone recounted in his diary “John and I breakfasted in company with a fellow traveller from whom we learned that he was a clergyman, and had been at Oxford – together with diverse particulars of his private affairs: a man apparently by no means void of talent.”

Gladstone married Catherine Glynne who was born at Hawarden Castle, Flintshire, in 1812, the daughter of an historic Whig family. Catherine’s mother was closely related to four different prime ministers. Having married Gladstone in 1839, Catherine went on to have eight children, and her life was focused on her family. Gladstone told her everything about his political life, and wrote to her frequently when they were apart.

In a career lasting over 60 years, Gladstone served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-consecutive terms (the most of any British prime minister) beginning in 1868 and ending in 1894. He also served as Chancellor of the Exchequer four times, for over 12 years.

As Chancellor William Gladstone pushed to extend the free trade liberalisations in the 1840s and worked to reduce public expenditures, policies that when combined with his moral and religious ideals became known as “Gladstonian Liberalism”.

Gladstone started out a staunch fundamentalist, espousing the ideas of his day, including supporting slavery. However, by 1840 he began to rescue and rehabilitate London prostitutes, actually walking the streets of London himself and encouraging the women he encountered to change their ways. He continued this practice decades later, even after he was elected Prime Minister.

In 1848 he also founded the Church Penitentiary Association for the Reclamation of Fallen Women.

In May 1849 he began his most active “rescue work” with “fallen women” and met prostitutes late at night on the street, in his house or in their houses, writing their names in a private notebook. He aided the House of Mercy at Clewer near Windsor and spent much time arranging employment for ex-prostitutes.

In 1927, during a court case over published claims that he had had improper relationships with some of these women, the jury unanimously found that the evidence “completely vindicated the high moral character of the late Mr W.E. Gladstone.”

Gladstone ‘rescued’ courtesan Laura Bell Thistlethwayte and remained her friend for thirty years. It is possible that this is the time that William Gladstone became acquainted with ‘alternative’ ideas, especially about homeopathy.

One of Laura’s first ‘conquests’ was William Wilde, the father of Oscar Wilde. William Wilde was favourably impressed with his tour of homeopathic hospitals in 1912.

After Laura Bell Thistlethwayte‘s death, amongst her possessions was found a large collection of letters written to her by Mr. Gladstone. Today these are housed in the Gladstone Library and Museum at Hawarden in North Wales, the country house of the Gladstone family.

Also with his work amongst prostitutes, Gladstone may well have met James Hinton and become an early advocate of slumming, which became most fashionable about this time, and attracted advocates such as Arnold Toynbee who was also heavily influenced by James Hinton.

James Hinton was a friend of homeopath Thomas Roupell Everest and his daughter Mary Everest Boole, the wife of George Boole. Victorian reformers drew inspiration from many sources, but it was James Hinton who most deeply and explicitly articulated how the problems of slum life and the attractions of slumming were enmeshed in a complex matrix of sexual and social politics.

Gladstone would also have known about Henry Mayhew and his groundbreaking work London Labour and the London Poor; a groundbreaking and influential survey of the poor of London, and also the work of Catherine and William Booth, who were firm advocates of homeopathy.

Gladstone believed that government was extravagant and wasteful with taxpayers’ money and so sought to let money “fructify in the pockets of the people” by keeping taxation levels down through “peace and retrenchment.”

When Gladstone first joined Henry Palmerston‘s government in 1859, he opposed further electoral reform, but he moved toward the Left during Henry Palmerston‘s last premiership, and by 1865 he was firmly in favour of enfranchising the working classes in towns.

In the 1860s and 1870s, Gladstonian Liberalism was characterised by a number of policies intended to improve individual liberty and loosen political and economic restraints. First was the minimization of public expenditure on the premise that the economy and society were best helped by allowing people to spend as they saw fit. Secondly, his foreign policy aimed at promoting peace to help reduce expenditures and taxation and enhance trade. Thirdly, laws that prevented people from acting freely to improve themselves were reformed….

The issue of disestablishment of the Church of Ireland was used by Gladstone to unite the Liberal Party for government in 1868. The Act was passed in 1869 and meant that Irish Roman Catholics did not need to pay their tithes to the Anglican Church of Ireland.

In 1880, he was Prime Minister again and Gladstone had opposed himself to the “colonial lobby” pushing for the scramble for Africa. He thus saw the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, First Boer War and the war against the Mahdi in Sudan.

He also extended the franchise to agricultural labourers and others in the 1884 Reform Act, which gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs – adult male householders and £10 lodgers – and added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections…

In 1886 Gladstone’s party was allied with Irish Nationalists to defeat Lord Salisbury’s government; Gladstone regained his position as PM and combined the office with that of Lord Privy Seal. During this administration he first introduced his Home Rule Bill for Ireland. The issue split the Liberal Party (a breakaway group went on to create the Liberal Unionist party) and the bill was thrown out on the second reading, ending his government after only a few months and inaugurating another headed by Lord Salisbury.

In 1892 Gladstone was re-elected Prime Minister for the fourth and final time. In February 1893 he re-introduced a Home Rule Bill. It provided for the formation of a parliament for Ireland, or in modern terminology, a regional assembly of the type Northern Ireland gained from the Good Friday Agreement.

The Home Rule Bill did not offer Ireland independence, but the Irish Parliamentary Party had not demanded independence in the first place. The Bill was passed by the Commons but rejected by the House of Lords on the grounds that it had gone too far.

On 1 March 1894, in his last speech to the House of Commons, Gladstone asked his allies to override this most recent veto. He resigned two days later, although he retained his seat in the Commons until 1895. Years later, as Irish independence loomed, King George V exclaimed to a friend, “What fools we were not to pass Mr. Gladstone’s bill when we had the chance!”

In 1895, at the age of 85, Gladstone bequeathed £40,000 and much of his library to found St Deiniol’s Library, (founded with the help of his brother in law Stephen Richard Glynne) in law the only residential library in Britain. Despite his advanced age, he himself hauled most of his 32,000 books a quarter mile to their new home, using his wheelbarrow.

In 1896 in his last noteworthy speech, he denounced Armenian massacres by Ottomans in a talk delivered at Liverpool.

Gladstone never quite left his fundamentalist roots, but Gladstone was a man of his time who nevertheless had many humanistic tendencies enshrined in what became known as Gladstonian Liberalism.

Hello, I am Lucy Bell, originally Lucy Thistlethwayte great great ? grandaughter of Laura Bell, I am trying to find out information about Gladstone, Hawarden House, Laura Bell, but also about the photographic side of Lady Hawardens life, and relationships.

I wonder if you can point me in the right direction. I am looking intor stereoscopy of the times