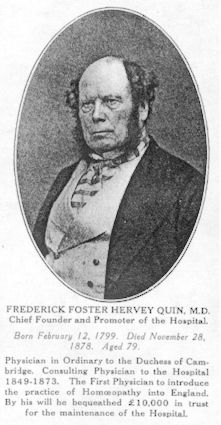

Frederick Hervey Foster Quin (MD Edin 1820) (12 February 1799 – 24 November 1879) was a British orthodox physician who converted to homeopathy to become one of the very first homeopaths in Britain. In 1844 he established the British Homeopathic Society with ten colleagues, which included Paul Francois Curie (grandfather of the scientist Pierre Curie), William Leaf, a rich London Silk Merchant, and Thomas Roupell Everest, the younger brother of Sir George Everest. These few had all been close confidants of Samuel Hahnemann during the last ten or so years of his life, and Quin had practiced homeopathy in Paris between 1831 and 1832. Quin was also a central figure in the establishment of the London Homeopathic Hospital.

Frederick Hervey Foster Quin (MD Edin 1820) (12 February 1799 – 24 November 1879) was a British orthodox physician who converted to homeopathy to become one of the very first homeopaths in Britain. In 1844 he established the British Homeopathic Society with ten colleagues, which included Paul Francois Curie (grandfather of the scientist Pierre Curie), William Leaf, a rich London Silk Merchant, and Thomas Roupell Everest, the younger brother of Sir George Everest. These few had all been close confidants of Samuel Hahnemann during the last ten or so years of his life, and Quin had practiced homeopathy in Paris between 1831 and 1832. Quin was also a central figure in the establishment of the London Homeopathic Hospital.

Frederick Hervey Foster Quin’s parentage is unknown, although some scholars believe his mother was Elizabeth Cavendish, the Duchess of Devonshire. He was a schoolboy in Putney, attending a school kept by the son of children’s author and educational reformer Sarah Trimmer. In 1817 he went up to Edinburgh University to study medicine under Andrew Duncan (1773 – 1832), noted for his extraction of cinchona from Peruvian Bark. Quin graduated with his MD in August 1820.

In December 1820 Quin traveled to Rome as personal physician to the Duchess of Devonshire. He remained with her in the city between March and July before moving to Naples in order to remain proximate when she no longer required his constant attendance. In Naples Quin set himself up in what quickly became a thriving practice and he made close connections with such figures as the archaeologist Sir William Gell, the Countess of Blessington, and the diplomat Sir William Drummond.

In 1823 Quin had an offer from Lord Byron to accompany him to Greece as his physician, but his health was too delicate to accept. The painter Joseph Severn was a ‘mutual friend‘ of Quin and the artist and lay homeopath Thomas Uwins. Severn sketched a portrait of Quin, Richard Westmacott and William Etty playing cards in Naples in 1823.

1824 began dreadfully for Quin. In January, he was brutally assaulted by a Neapolitan coachman and nearly lost his life. Then in March he returned to Rome to attend the Duchess in her final illness. He travelled to England later in 1824 where he met Robert Grosvenor, 1st Baron Ebury, Sir Ferdinand Richard Edward Dalberg-Acton, and Thomas Uwins.

Back in Naples in 1825, Quin became acquainted with homeopath Georg von Necher who appears to have been responsible for Quin’s conversion to homeopathy, and he travelled to Leipzig to visit him, also meeting another homeopath, Chevalier Lichtenfels. In Berlin, he was introduced to several other homeopathic physicians and as a result resolved to visit Samuel Hahnemann himself at Köthen.

On the way to Köthen, Quin became very ill and was treated successfully with homeopathy, and he reported to his friend Thomas Uwins that his cure did not involve ‘any blood letting, no purges, no sudorifics and no blisters’, and he recovered after three days having taken ‘only five small powders’. Quinn was a lifelong asthmatic, which was eased by homeopathic treatment.

In 1826, he met with homeopath John Ernst Stapf and Samuel Hahnemann, and in 1827 he was appointed as physician to Queen Victoria’s uncle, Leopold of Saxe-Coburg (Later King Leopold I of Belgium). Some sources report that Quin was Leopold’s physician as early as 1824, when he came across homeopathy after one of the prince’s household became seriously ill, only to be cured by homeopathy.

In 1831, Quin traveled to Germany to treat a cholera epidemic, and despite catching it himself, he worked through the epidemic until it ceased, to be warmly praised by the local Mayor. Quin successfully cured himself of cholera on Samuel Hahnemann’s advice.

His reputation greatly enhanced, Quin published a paper on cholera, and his friends persuaded him to return to London, which he did in 1832, settling at 19 King Street, St James‘s. His practice flourished, which caused uproar in the Royal College of Surgeons. Quin calmly ignored them and continued his work, no doubt secure in the knowledge that he had the support of many notable figures in British society.

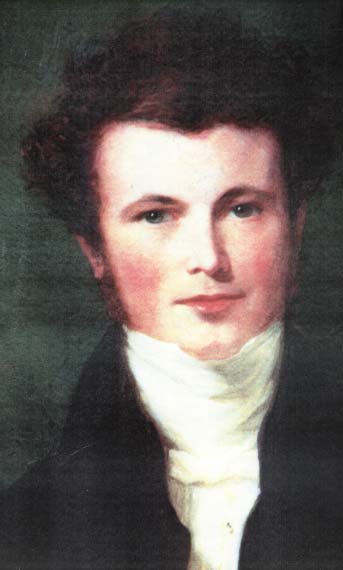

Frederick Foster Quin, Lithograph by E. Morton. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

As a young man, Quin was a very popular socialite and wit on the fashionable London circuit, a great friend of Charles Dickens amongst many others, and no society party, or social gathering, it was said, was complete without him.

By nature of a very pleasing disposition, he was a man of great personal charm. He was also latterly one of the regular dining partners of Edward VII.

The fact that many of the German relatives of the British Royal family were also devoted patrons of homeopathy, including Queen Adelaide, wife of King William IV, also assisted its rapid social acceptance in Britain.

Rich patrons of homeopathy, for example the first Marquis of Anglesea, Henry William Paget, companion at Waterloo of Arthur Wellesley 1st Duke of Wellington, not only formed its client base, but also funded and dominated the committees which ran the many homeopathic hospitals and dispensaries of the nineteenth century.

During this time, Quin became personal physician to other influential figures, including the Duke of Beaufort, and in 1833, he moved to 13 Stratford Place, where he worked industriously, writing, consulting and keeping up a constant correspondence with his friends and his homeopathic colleagues abroad, including Moritz Wilhelm Mueller.

Quin’s reputation continued to grow and he met, treated and taught a great many people, often being consulted by other doctors who were eager to learn about the new art of homeopathy. Some of these many influential converts to homeopathy included Charles Mansfield Clarke 1st Baronet, James Clark, Edward Bulwer Lytton, William Makepeace Thackeray, Edwin Henry Landseer, Richard Robert Madden, Thomas Moore, William Charles MacReady, Charles James Mathews, John Forster, William Charles Ellis, Samuel Lover, Albany William Fonblanque, and many others.

Quin now also had homeopathic colleagues to assist him, including Guiseppe Belluomini, Harris F. Dunsford, Paul Francois Curie and Hugh Cameron. In 1836, Sir William Charles Ellis, the Medical Superintendent of the Hanwell Middlesex County Pauper and Lunatic Asylum, invited Quin and his colleagues Harris F. Dunsford, and Paul Francois Curie to dinner in order to learn more about homeopathy. Ellis, a pioneer of humane, moral treatment, “Had recently heard of the system of Homeopathy “and conceiving that it may be useful amongst the patients of this Institution” sought further information. Ellis was clearly impressed and used homeopathy in the treatment of several of his patients at Hanwell. This open-minded attitude towards homeopathy was continued at Hanwell by Ellis’ successors, Dr.s John Conolly and John Gideon Milligan, and the Chairman of the Asylum in the 1840s was Charles Augustus Tulk 1786 – 1849, a close colleague of homeopathic doctor James John Garth Wilkinson.

Although Quin’s charisma, contacts, and capabilities as a physician ensured that homeopathy quickly made many converts, orthodox medical opposition was marked from the moment of his arrival in the capital. The Royal College of Physicians had the ancient power to control all medical practice within seven miles of the City of London, although it had not exercised this right for a century. It called upon Quin, an Edinburgh graduate, to take the college examination. He ignored the summons and eventually the College lost its nerve and desisted. But he was not forgotten.

In 1836 the famed opera singer Maria Malibran, a patient of Quin’s friend Guiseppe Belluomini, died causing a storm of criticism against homeopathy. This polarised people, but homeopathy emerged from these attacks all the stronger.

In response to urging from his European colleagues and as a result of the vitriolic attacks on homeopathy, Quin and his friends and colleagues Guiseppe Belluomini, Harris F Dunsford, John Epps, Paul Francois Curie,Thomas Uwins, William Kingdon, Hugh Cameron, William Headland, Walter Cooper Dendy, and Edward Hamilton began to plan the creation of what would become The British Homeopathic Society.

Quin also set in motion the foundation of a London Homeopathic Dispensary with the aim of relieving the suffering of the poor and offering an opportunity to witness homeopathy in action to “interested parties.”

Homeopaths began to offer their time for free in rotation, attending the poor in their homes and forcing a consultation with allopathic physicians – all supported by voluntary contributions from friends of homeopathy.

Predictably, people rushed to help. Lord Elgin recommended his friend Dr. Scott from Glasgow, “an ardent student of homeopathy” to see Quin. Amos Gerald Hull wrote from New York, sending George Butler to see Quin with some journals, and with a promise from Constantine Hering to send over all the published documents from America, and sending over articles in defense of homeopathy. Hull also sent over the preamble to the constitution of the New York Homeopathic Society, pointing out new provings of American plants for Quin’s delectation.

Despite the support and goodwill, a number of orthodox medical men continued their truculent opposition to homeopathy, often targeting Quin. In 1838 Quin was proposed for membership of the Athenaeum Club, an exclusive gentlemens’ club. Another member, the then President of the Royal College of Physicians, Dr. Paris, publicly called him a quack. This slur was only retracted on pain of a duel, but the College still mobilised its supporters to ensure that Quin was blackballed.

Here is a small anecdote, related to Frederick Hervey Foster Quin. When Dr. John Ayrton Paris (1785-1856), then President of the Royal College of Physicians, noted seeing Frederick Hervey Foster Quin’s name in the list of candidates to the Athenaeum Club in London, he remarked that they had come to a sorry state if ‘quacks and adventurers’ were to be proposed as members.

Lord Clarence Paget, an officer in the Guards, visited some days later Paris. Lord Paget requested him either to provide a written apology for his language concerning Frederick Hervey Foster Quin or else justify it with pistols.

John Ayrton Paris was forced, not willing to try Lord Clarence Paget’s skills in shooting, to sign a retraction of his views, and an apology.

Quin also had the last laugh over the Athenaeum Club as James Epps, homeopathic chemist and the founder of the great cocoa business associated with his name , provided foodstuffs for the Athenaeum Club, who did not distinguish themselves when they prevented Quin from becoming a member, but were quite happy to munch on ‘homeopathic confectionaries!’ Further, Quin’s name had become even more widely known as a result of the incident, leading the Marquis of Anglesea to write and congratulate Quin on ‘his defeat’ of his opponents.

In 1839, Quin completed a translation of Hahnemann’s Materia Medica Pura, but a fire at his printers destroyed everything, and Quin’s poor health prevented him repeating this momentous task for a second time. Although he did not contribute any further written material to the homeopathic corpus, Quin’s hard work as a physician and his strenuous efforts to popularize and institutionalize homeopathy ensured his legacy as one of homeopathy’s most significant individuals.

As a direct result of his efforts there was an influx of recruits to the cause of homeopathy. From 1839 Francis Black, John James Drysdale, Robert Ellis Dudgeon, C B Kerr, John Chapman, Stephen Yeldham, Joshua Lambert Vardy, Edward M Madden, Henry R Madden, Edward Charles Chepmell and many others joined the movement. Charles W. Luther was already established in Ireland and remained in constant correspondence with Quin.

In 1840, Quin moved to Arlington Street, and in 1843, he established the St. James’s Homeopathic Dispensary, numbering amongst his patrons the Queen Dowager Adelaide and the Duke of Beaufort.

In 1844, Quin founded the British Homeopathic Society to replace the Hahnemannian Society which he had tried to bring to life in 1837. Quin was the first President of the British Homeopathic Society. Thus followed blast and counterblast between homeopaths and allopaths which ultimately led to a boom of homeopathy in Britain.

From 1845, Quin became the personal physician of the Duchess of Cambridge.

By 1850 Quin’s most ambitious objective had been realized in the founding of a London Homeopathic Hospital. Thanks largely to his hard work, this centre for clinical teaching had been established initially at Golden Square, before moving to its permanent home in Great Ormond Street:

Dr. Quin himself collected an enormous sum of money from his influential friends for its endowment, and from his having initiated the idea of a hospital, and having done so much to carry out his project, he must always be regarded as its founder.

In 1851, Quin was appointed President and Chair of the Homeopathic Congress in Paris,

In 1853, Quin, George Atkin, John Chapman and Robert Ellis Dudgeon, John Rutherford Russell, James W Metcalfe and an anonymous ‘friend’ put together a Directory of British and Foreign Homeopaths and their supporters to counter the suppression of all mention of homeopaths and their supporters by the editors of the London and Provincial Medical Directory,

In 1858, Quin and his homeopathic colleague Thomas Vernon Bell (1824-1905), were joined in consultation by an allopath Dr. Fergusson, to attend Henry Charles FitzRoy Somerset 8th Duke of Beaufort, much to the consternation of The Lancet (Anon, The Lancet 1858; Medical Times and Gazette, Volume 16, 1858). Intriguingly, The Lancet redacted any mention of Frederick Foster Hervey Quin from their version of this letter, presumably because of the influence that his name carried.

In 1859, Quin was appointed Chair of Therapeutics and Materia Medica at the London Homeopathic Hospital

On top of all that Quin had done to promote and integrate homeopathy in Britain, arguably his most enduring achievement came in 1858:

Through his many influential contacts in the world of politics, for example Robert Grosvenor, Quin was able to obtain an amendment to the 1858 Medical Act, withholding a recommendation about the type of medicine approved in Britain.

As a result of this skillful manouevre, homeopathy was indirectly tolerated without challenge and thus never censured by Parliament as an unacceptable or deviant mode of medical practice…

‘Quin was able to obtain an amendment to the Medical Registration Bill; a clause was added enabling the Privy Council to withdraw the right to award degrees from any university that tried to impose the type of medicine practised by its graduates.’

The 1858 Medical Act established for the first time the professional status and legal regulation of formally qualified medical practitioners, as distinct from quacks, and still regulates the practice of medicine in the UK today. The law was specifically designed to outlaw quackery, which was rife at that time, by establishing a Register of approved practitioners. Initially these guidelines were interpreted very strictly, confining those on the Register only to holders of UK medical degrees, licenses and diplomas.

Even the holders of Continental medical degrees and diplomas were excluded from the Medical Register, for fear of encouraging deviant forms of medical practice in Britain, ie. quackery. In more recent times these rules were relaxed, even allowing American medical graduates the right to practice, whose degrees had previously been scorned as worthless pieces of paper.

The success of the London Homeopathic Hospital in treating patients afflicted by the 1854 cholera outbreak was a crucial factor in securing Quin’s amendment to the 1858 Medical Act that ensured properly qualified doctors could not be denied admission to the new register based on their practicing of homeopathy.

From Arlington Street he moved to Mount Street, where his health began to fail, and compelled him to retire to a considerable extent; so that from the time he left Mount Street he never laid himself out for practice, albeit he continued to see those patients who would consult no one but himself, seeing such an one but a few days before his last illness.

On leaving Mount Street, Granville Leveson Gower, 1st Earl Granville, who entertained the warmest friendship and admiration for Frederick Hervey Foster Quin, invited him to live at his lordship’s house in Brunton Street; after residing there a short time, and during a very severe illness, he removed to Belgrave Mansions; here he remained till his lease expired. While looking for other quarters, Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, then abroad, wrote to him, begging him to occupy apartments at Clarence House.

The Duke of Sutherland made a similar offer of Stafford House for his use; he accepted the gracious offer of Alfred Duke of Edinburgh, and resided at Clarence House till the Duke and Duchess returned to town, when, although pressed to remain, he took a suit of rooms in Queen Anne’s Mansions, where he died at the advanced age of seventy nine.

Quin had struggled with his own health since he was young and over the next two decades it deteriorated further. Still he continued to advocate for homeopathy, even cautioning against efforts to seek titles for leading homeopathic practitioners, seen by some as a way to increase the prestige of the movement. Quin understood that the same aristocratic patronage that had secured the survival of homeopathy in Britain also worked against it when the general public associated it with the upper classes. Conferring titles such as knighthoods on homeopaths, he explained, would only undermine the cause of homeopathy.

Nevertheless, Quin remained personally close to some of the most distinguished figures in British and European society. When he became ill at the end of his life Edward, The Prince of Wales and the future King Edward VII was at his bedside. As a measure of the respect and affection with which he regarded Quin, Edward VII sent four empty horse drawn royal carriages to join the cortege at his funeral, probably the highest honour ever paid by a Royal to a commoner.

Quin’s personal papers are in the Royal Archives.

Quin is buried at London Kensal Green Cemetery.

Quin was the homeopathic physician of the Duchess of Devonshire, Leopold I Belgium, Queen Dowager Adelaide, Alfred Duke of Edinburgh, Gilbert Elliot Murray Kynynmound 2nd Earl of Minto, George Granville William Sutherland Leveson Gower 3rd Duke of Sutherland, Arthur Algernon Capell 6th Earl of Essex, Lord Ronald Charles Sutherland Leveson Gower, Keppel Richard Craven, Charles Dickens, William Drummond, Albany William Fonblanque, John Forster,Edwin Henry Landseer, Edward Bulwer Lytton, Count d’Orsay, William Charles MacReady, William Makepeace Thackeray, Lucia Elizabeth Vestris, Edward Charles Warde. There were also many Campbells who consulted Quin.

Frederick Hervey Foster Quin was himself a patient and a personal friend of the surgeon William Fergusson 1st Baronet.

Frederick Hervey Foster Quin was a friend of Henry William Paget, 1st Marquis of Anglesey, Captain Henry Charles FitzRoy Somerset, 8th Duke of Beaufort, George Boole, Francis Burdett, Abbe Campbell, Baroness E C de Calabrella, the Chalon family, Charles William Bury, 2nd Earl of Charleville, Mary Deerhurst Lady Coventry, Charles Dickens, Richard Whately, Archbishop of Dublin, King Edward VII, Frederick Faulkner, William Tilbury Fox, Robert William Gardiner, William Gell, Augustus Bozzi Granville, George Gulliver, Mary Augusta Fox Holland, Theodore Edward Hook, Charles Powell Leslie, Robert Liston, Charles Locock 1st Baronet, Charles James Mathews, James More Molyneux, Lieutenant General Henry Robinson Montagu, 6th Baron Rokeby, Augustus Henry Moreton, Moritz Wilhelm Mueller, John Ponsonby 1st Viscount Ponsonby, Joseph Severn, Thomas Uwins, Arthur Wellesley 1st Duke of Wellington, David Wilkie, John Yate Lee and many others.

Frederick Hervey Foster Quin was a colleague of Victor Arnaud, George Atkin, James Smith Ayerst, William Bayes, Hugh Cameron, Francois Cartier, John Chapman, Edward Charles Chepmell, Paul Francois Curie, Julien Aimé Davet de Beaurepaire de Benery, Antoine Hippolyte Desterne, William Vallancy Drury, John James Drysdale, Robert Ellis Dudgeon, George Napoleon Epps, Thomas Roupell Everest, James Goodshaw, Arthur Guinness, Edward Hamilton, Frantz Hartmann, Amos Henriques, Richard Walter Heurtley, George James Hilbers, George Calvert Holland, Richard Hughes, F. W. Irvine, Henry Kelsall, Claude Buchanan Kerr, Joseph Kidd, Thomas Robinson Leadam, William Leaf, James Loftus Marsden, Victor Massol, Jas Bell Metcalfe, Thomas Morecroft, George Newman, Samuel Thomas Partridge, Antoine Henri Petroz, Alfred Crosby Pope, Joseph Hyppolyte Pulte, John Hodgson Ramsbotham, Henry Reynolds, John Rutherford Russell, Marmaduke Blake Sampson, Léon Francois Adolphe Simon, Jean Paul Tessier Senior, Daniel Spillan, Charles Caulfield Tuckey, Joshua Lambert Vardy, Arthur de Noe Walker, Charles Wenicke, Dionysious and Severin Wielobycki, Phillip Mann Wilmot, David Wilson, George Wyld, Stephen Yeldham and many others.

Select Publications:

- Dissertatio medica chemica inauguralis de arsenico (1820).

- Du traitement homoeopathique du choléra, avec notes et appendice (1832).

- Pharmacopoeia homoeopathica (1834).

Edward Hamilton wrote A Memoir of Frederick Hervey Foster Quin (1879).

Sue,

Your work is always a real pleasure to read.

Please note that you have referenced an oft-repeated assertion that Dr. Quin was asked to come to France to treat Napoleon I. Whether it is true or not, it is important to note that this request came BEFORE Quin began to study or practice homeopathy (Napoleon died in 1821!).

–Dana

Great work Sue.

When I was lecturing in Naples in the 1980s, I met with homoeopaths who reminded me that Quin was introduced to homoeopahty in Naples. he was on the Grand Tour, met with Dr Necker . Whe he took ill he was treated in the Trinity Hospital with homoeopathy and this was his first experience. He later returned to England and set up practice with an Italian doctor, Guiseppe Belluomini. a partenership that lasted some 12 years.

I just sent you a picture of a handsome Quin aged between the youthful and the senior portraits you already have.